6 Things to Know About the China Export Controls (Part 2 of 2)

Amid heightened geopolitical tensions between the United States and China, we are devoting two articles to helping the academic and research organizations dissect 6 of the essential items under the new U.S. export controls related to China.

In Part 1, we explored the complexities created by the new Commerce Department requirements. In Part 2, we will further expand on BIS’ activities and navigate the additional requirements of OFAC and the Department of Defense. We will also cover some enforcement cases to help illustrate what the authorities expect from organizations and their employees in terms of compliance. (Check out Part 1 here if you haven’t read it yet.)

#4: OFAC’s Transformative Year

The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) witnessed a transformative year in 2021. As the Biden Administration’s political team stepped into leadership at the Treasury, it conducted a comprehensive sanctions review and began developing its own sanctions policy priorities.

Here are some of the significant developments:

![]()

Chinese Military Companies

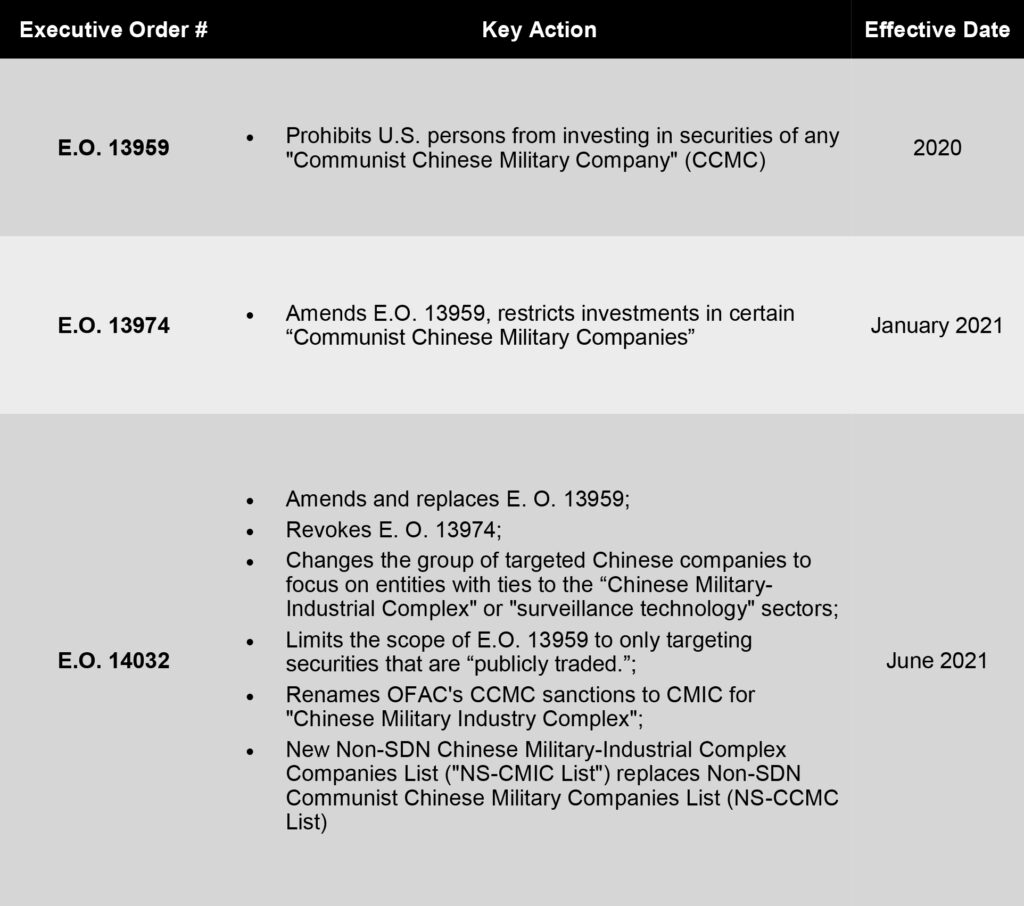

In January 2021, President Trump issued Executive Order (E.O.) 13974, amending a vague and somewhat confusing E.O. 13959 that was initially issued in November 2020. E.O. 13959 was the original E.O. that prohibited U.S. persons from investing in securities of any “Communist Chinese Military Company” (CCMC). However, its impact was confusing because two designated entities were able to sue in the Washington D.C. District Court challenging their designation and were successful in obtaining preliminary injunctions against the U.S. government.

In June 2021, President Biden further amended E.O. 13959 by issuing E.O. 14032, “Addressing the Threat from Securities Investments that Finance Communist Chinese Military Companies.” The Biden Administration substantially modified restrictions on U.S. person investments in some China-based companies. The new restrictions focused mainly on entities with ties to the Chinese “military-industrial complex” or “surveillance technology” sectors.

This new E.O. and its related OFAC guidance provided helpful clarity on OFAC’s CCMC sanctions (which were renamed CMIC for “Chinese Military Industry Complex”). At the same time, OFAC created and published a new Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (“NS-CMIC List”) under EO 14032. These series of E.O. could be summarized in the table below.

Effective June 3, 2021, the NS-CMIC List replaced and superseded in its entirety the Non-SDN Communist Chinese Military Companies List (NS-CCMC List), which has been deleted from OFAC’s website. Only entities whose names exactly match the names of the entities on the NS-CMIC List are subject to the prohibitions in E.O. 13959, as amended.

68 Chinese companies are listed on the NS-CMIC List (including name variants for 205 entries), focused mainly on high-tech sectors such as aerospace, artificial intelligence, electronics, defense, technology, and telecommunications.

COMPLIANCE CONNECTION: This means that U.S. persons are prohibited from purchasing or selling publicly traded securities or any publicly traded securities that are derivative or designed to provide investment exposure to such securities with such parties. U.S. persons may engage in other activities related to parties on the NS-CMIC List. For example, you may still purchase and sell goods or services related to NS-CMIC entities and their subsidiaries.

For U.S. academic and research entities exploring overseas research talent, a past affiliation with entities listed in the NS-CMIC List, does not necessarily mean that the researcher cannot be hired.

It is generally worth noting, however, that if the party or academic researcher is an SDN, the broader prohibitions on U.S. Persons engaging with SDNs apply and override the more limited prohibitions for the NS-CMIC List. U.S. persons are forbidden from engaging in any transactions with an SDN, their property interests, or entities 50% or more owned by the SDN.

Xinjiang Region

In 2021, as part of a more comprehensive whole-of-government approach, OFAC addressed perceived human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) and elsewhere in China. Several agencies were involved:

- Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS): In July 2021, decrying “Beijing’s campaign of repression, mass detention, and high-technology surveillance against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and members of other Muslim minority groups in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regions of China, where the [People’s Republic of China] continues to commit genocide and crimes against humanity,” BIS added 14 China-based companies connected to Xinjiang to its Entity List. BIS added another five entities directly supporting China’s military modernization programs related to lasers and C4ISR programs to the Entity List.

- That same month, BIS, the Department of Homeland Security, Department of State, and Department of Treasury issued an updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory highlighting compliance risks for continued dealings involving Xinjiang in the context of widespread forced labor and other egregious human rights abuses.

COMPLIANCE CONNECTION: This advisory warns that “businesses and individuals that do not exit supply chains, ventures, and/or investments connected to Xinjiang could run a high risk of violating U.S. law.”

- On December 16, 2021, OFAC sanctioned eight Chinese technology firms pursuant to Executive Order (E.O.) 13959, as amended by E.O. 14032. These eight entities actively support the biometric surveillance and tracking of ethnic and religious minorities in China, particularly the predominantly Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang. All eight companies had been previously added to the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Entity List. The entities are Cloudwalk Technology Co., Ltd.; Dawning Information Industry Co., Ltd.; Leon Technology Company Limited; Megvii Technology Limited; Netposa Technologies Limited; Xiamen Meiya Pico Information Co., Ltd.; Yitu Limited, and SZ DJI Technology Co. Ltd (aka DJI, the world’s largest drone manufacturer).

- On the next day, BIS added 37 parties to the BIS Entity List, including 25 Chinese companies, for their alleged involvement in efforts to develop and use biotechnology and other technologies for military application and human rights abuses. Most of the designated parties reside in China, with certain parties located in Georgia, Turkey, and Malaysia.

COMPLIANCE CONNECTION: The designations by BIS generally prohibit the export, re-export, or in-country transfer of commodities, software, and technology subject to the Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”), including EAR99 items, to designated entities without a license. BIS will review export licenses under a “presumption of denial” policy, and no license exceptions are available.

- On Human Rights Day, OFAC added four current and former Chinese government officials connected to Xinjiang to its List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List and a related top facial recognition firm over Uyghur concerns SenseTime Group Limited to the NS-CMIC List. SenseTime 100 percent owns Shenzhen SenseTime Technology Co. Ltd., which has developed facial recognition programs that can determine a target’s ethnicity, focusing on identifying ethnic Uyghurs. Shenzhen Sensetime Technology Co. Ltd. has highlighted its ability to identify Uyghurs wearing beards, sunglasses, and masks when applying for patent applications.

- OFAC signaled that it “expects to use its discretion to target, in particular, persons whose operations include or support, or have included or supported, (1) surveillance of persons by Chinese technology companies that occurs outside of the PRC; or (2) the development, marketing, sale, or export of Chinese surveillance technology that is, was, or can be used for surveillance of religious or ethnic minorities or to otherwise facilitate repression or serious human rights abuse.”

- Tough new U.S. regulations on the import of goods from the Xinjiang region of China came into effect on June 21, 2022. U.S. Customs and Border Protection began enforcing the Uighur Forced Labour Prevention Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law in December 2021. Under the rules, firms have to prove imports from the region are not produced using forced labor.

COMPLIANCE CONNECTION: Compliance officers should be mindful of the nexus of technology firms transacting with China, particularly Xinjiang-based companies. It is recommended to conduct due diligence to assess potential indirect risks – i.e., where the ultimate beneficiary may be a surveillance or technology company associated with Xinjiang.

Companies should assess whether their export compliance programs include appropriate measures that address the risks associated with dealing with parties on OFAC’s NS-CMIC and SDN lists and the Entity List. It is worth considering that the passage of the Uyghur Act could lead to additional sanctions, which could require updated restricted party screening procedures, supplier/customer onboarding processes, and due diligence assessments. Importers of goods from China will need to conduct enhanced due diligence to prove imports from the region are not produced using forced labour.

![]()

#5: U.S. Department of Defense

In parallel, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) released on June 3, 2021, its List of “Chinese Military Companies” (CMC) per the statutory requirement of Section 1260H of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of 2021.

The DoD strategy focuses on countering China’s Military-Civil Fusion development strategy, which supports the modernization goals of China’s People’s Liberation Army by ensuring its access to advanced technologies and expertise acquired and developed by companies, universities, and research programs that appear to be civilian entities.

Section 1260H directs the DoD to identify, among other things, Military-Civil Fusion contributors operating directly or indirectly in the United States.

It is worth noting that initially, as envisioned by Congress, it was the DoD who took the lead in selecting and designating CCMCs. Still, the Trump Administration tasked OFAC to implement E.O. 13959’s investment restrictions, thereby leading to considerable confusion between those two federal agencies on the division of the roles.

For example, many Chinese companies with publicly traded securities had close but not exact matches to entity names on DoD’s CMC List. It was also unclear whether a designation by DoD would apply to every owned subsidiary or controlled by a named CMC entity.

President Biden’s E.O. 14032 sought to clarify some of the regulatory confusion caused by Trump’s E.O. 13959, applying OFAC’s financial sanctions against transactions involving publicly traded securities of entities on DoD’s List.

Ultimately, E.O. 13959, as amended, shifts the primary authority for designating CMICs from DoD to the Treasury Department.

COMPLIANCE CONNECTION: What does this mean for exporters in terms of compliance? As explained in Part 1 of this article, even if the party is not listed on BIS Military End User (MEU) or Entity Lists but is listed in OFAC’s Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (“NS-CMIC List”) or the DoD “List of Communist Chinese Military Companies” (the “DoD List”), such listings would raise a Red Flag under the EAR. The exporter may require additional due diligence to determine whether a license is needed under the MEU rule.

![]()

#6: Highlighting Enforcement Cases and Looking forward

It is worth noting that the U.S. plans to raise penalties against companies that don’t comply with export control rules that threaten National Security, according to a top Biden administration official.

Companies breaking the rules might face more burdensome consequences, according to Axelrod, Assistant Secretary for export enforcement at BIS, who outlined the new BIS strategy in a speech to the Society for International Affairs on May 16, 2022.

The proposed new penalties include:

- BIS publicly disclosing, by releasing letters, which companies it is investigating for export control violations when an investigation is opened, not when it is resolved, often years later, so that other companies can see in real-time what kind of behavior to avoid.

- Forcing companies to admit wrongdoing if they are found to have violated export control laws. BIS is considering a requirement for companies that settle before a trial to avoid stiffer penalties to admit to facts of the case publicly. That would send a transparent deterrent message, rather than the current “no admit/no deny” settlements that don’t require an admission of misconduct.

- Increasing financial penalties for violations to make sure they are high enough to punish rule-breakers and deter violators. BIS wants companies to invest in compliance rather than conclude that they’d be comfortable with a fine in their cost-benefit analysis.

BIS is empowered with administrative enforcement — a separate process from a Justice Department investigation that can result in criminal penalties. However, according to Axelrod, “BIS administrative authorities can result in nearly the same punishment that a criminal conviction would bring”. That includes significant monetary penalties, agreements requiring a compliance overhaul, and, in extreme cases, denying a company’s ability to export. Axelrod reminds us that BIS administrative authorities can be just as powerful as criminal authorities when it comes to cases against companies.

In its most recent enforcement dated June 08, 2022, BIS issued a Temporary Denial Order (TDO) suspending the export privileges of three U.S.-based companies that allegedly sent blueprints for satellite, rocket, and defense prototypes to China without BIS authorization. This type of information is subject to strict U.S. export controls due to its sensitivity and importance to U.S. national security.

BIS said the three U.S.-based companies would be banned from exporting for 180 days, with an option to renew the 180-day export suspension.

The Department said Quicksilver Manufacturing, Rapid Cut, and U.S. Prototype received technical drawings and blueprints from U.S. customers and sent them to manufacturers in China for 3D printing.

“Outsourcing 3-D printing of space and defense prototypes to China harms U.S. national security,” Axelrod said in a statement. He reinforces this point by saying “By sending their customers’ technical drawings and blueprints to China, these companies may have saved a few bucks, but they did so at the collective expense of protecting U.S. military technology.”

Bottom Line

The importance of systematically checking your partners, customers, collaborators, and clients against the following restricted lists is more important than ever.

- OFAC NS-CMIC list

- OFAC SDN list

- BIS Entity List

- BIS MEU list

- DoD “Chinese Military Companies” (CMC)

Demonstrating due diligence in your operational compliance processes goes a long way in mitigating fines and penalties if an inadvertent violation occurs.

This article is Part 2 of the China Export Control Compliance Series. Part 1 of the series focused on BIS requirements, and Part 2 focused on OFAC and the Department of Defense.